Technology support, people as success factors and new areas of tension

The challenges: VUCA world, dynamic markets, digitalization

The current challenges for companies and organizations can be outlined with three keywords: VUCA world (e.g., Covid-19), dynamically changing markets and framework conditions (e.g., Brexit) and advancing digitalization (e.g., Robotic Process Automation). Companies and organizations are therefore required to be agile, to position themselves correctly in rapidly changing markets, to act in a customer-centric manner and to ensure efficient processes.

This results in key challenges for the education sector and education managers. In particular, employees in a wide variety of roles and with a wide variety of profiles must be empowered for new tasks and processes. This is made more difficult by the fact that the target groups of L&D are becoming increasingly heterogeneous: Professional and educational biographies have been becoming more “colourful” for many years and this also applies to entire workforces (due to expansion into international markets as well as migration movements).

In addition, the staffing of educational areas is not keeping pace with this growing complexity. At Hilti, for example, in 2015 only 16 learning professionals were responsible for providing training for 29,000 employees in 120 countries and 34 languages (cf. Kara I., 2020).

Empowerment, platforms, and personalization

In many places, we see progress on changing organizational and business models for L&D. For example, with content strategies that focus on user-generated content (UGC). Or, with the promotion of various forms of informal learning, with the allocation of time and budgets for self-directed learning activities, and, in general, with the provision of more employee responsibility with regards to their own qualification and employability.

Another approach is to create large libraries of digital content and make it available to employees (e.g., linkedin learning) and/or to introduce learning experience platforms or LXP (e.g., degreed, edcast, valamis or fuse universal). These content libraries and learning experience platforms offer enormous potential. They not only offer a “one stop shop” for an enormous amount of learning content, but also enable personalized learning content, i.e. a compilation of relevant content based on affiliations, roles, interests, and recommendations from the network or learning history. And the relevance of content is known to be an important driver of learning motivation (cf. the ARCS model by Keller 1987).

The limits of technical solutions

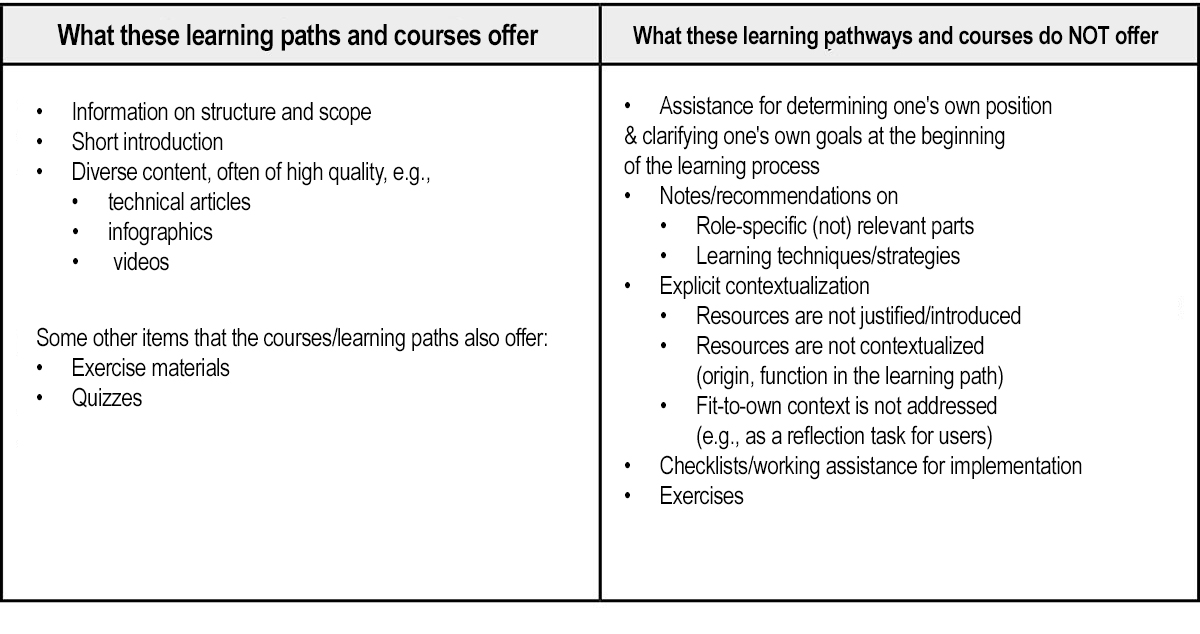

The introduction of these libraries and platforms usually involves considerable investment. At the same time, they are not the whole solution. Appropriate framework conditions are needed so that their potential can be exploited, and actual added value can be realized. If one takes a closer look at the learning paths and courses on these platforms, it becomes clear that there is a danger that only redundant knowledge is developed here, but no competence for action.

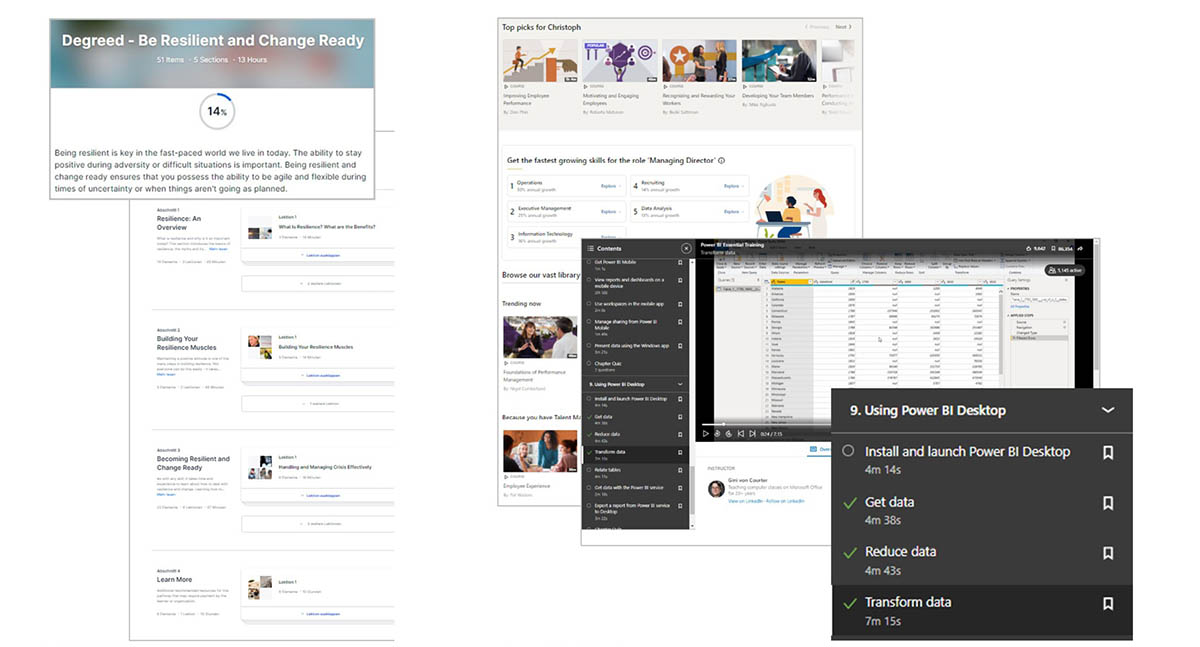

Two examples can help illustrate this: the learning path “Be resilient and change ready” on degreed.com; and the course “Power BI essential training” on LinkedIn Learning. An analysis of these two shows what they offer and what they do not:

To avoid misunderstandings: these two offers are well-made and they contain high quality elements. And the platforms behind them offer, in principle, the possibility of displaying these offers precisely to the employees for whom they are relevant. But for this to result in real capacity on the part of the users and for this to result in an increase in performance for the companies/organizations, more efforts are needed.

Roles relevant to success

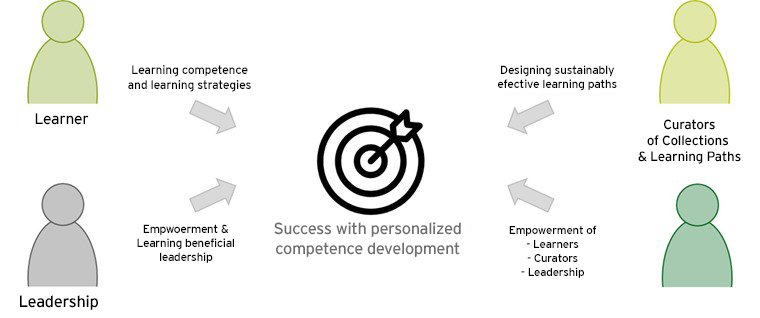

Curators need to be able to put themselves in the shoes of the users/learners and to integrate targeted elements that support the learning process on the part of the users (through orientation; through encouragement; through visible first intermediate successes; etc.). They need to understand the learning competence and learning techniques of those who work with the contents: setting personal goals; creating suitable learning situations; recognizing essentials; condensing information; applying what has been learned in one’s own context; reflecting on experiences and further adapting one’s own practice. That being said, leaders who specifically and effectively support their staff in lifelong learning in their field of work (e.g., by giving them freedom; by supporting them in formulating goals or implementing them in the field of work; etc.) are essential.

There are four roles in particular that are especially important for the success of technology-supported initiatives for personalized competence development:

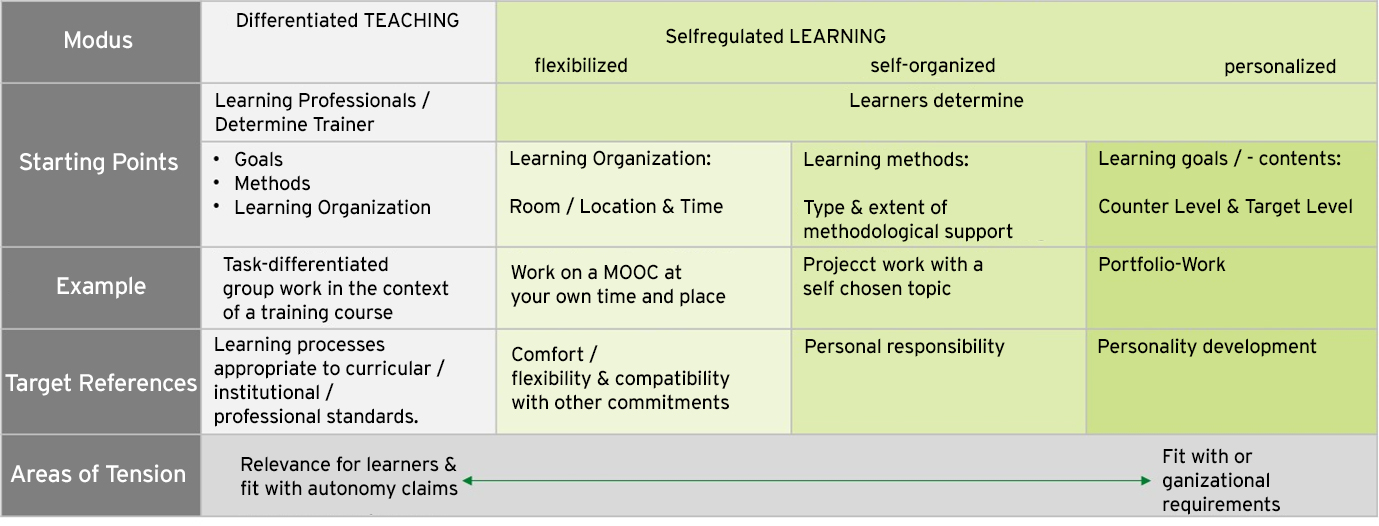

Personalization: Target references and areas of tension

Personalized learning and personalized competence development can be seen as the antithesis of classical teaching processes controlled by teachers – even if these address the challenges associated with diversity and heterogeneity via internal differentiation (cf. Euler 2018). In differentiating teaching, control over essential aspects of the teaching-learning process still lies with those responsible for education (conception, media design, implementation). Objectives, methods, and organization of learning are largely defined by those responsible for education. Diversity of the participants (and their specific prerequisites, interests, concerns) can be absorbed, for example, through different options for differently oriented group assignments (e.g. differentiating assignments for participants from different functional areas or with little/much experience in the topic. However, with all differentiation, the curricular, institutional or professional target references are clearly in the foreground and the participants should accept them.

At the other end of the spectrum is personalized learning. Here, learners not only define aspects of learning organization (e.g., place, time) and learning methods (e.g., mutual feedback in a working group) but also define the goals and the content. For example, learning and practicing “sketchnoting” as a working technique instead of practicing the protocol-creation with Microsoft Teams and its Decisions extension. Aspects of personality and personal development are more visible («I can create protocols that are easier to understand this way»). This is not only associated with high motivation potential («My goals») and a high potential for self-organization («I will take care of it myself»). It is also potentially linked to areas of tension with organizational requirements and personnel development («We use Microsoft Teams and its Decisions extension for taking protocols and offer user workshops on this»).

From differentiation via personalization to culture and value development

Enabling and promoting personalized learning activities and personalized competence development can, on the one hand, release great motivational potential. If employees can self-regulate their learning on the topics and content they perceive as relevant, then it is to be expected that the motivation to learn will be high. If the appropriate platforms and content are also available and the employees have the necessary learning competences and learning strategies, the conditions for sustainable learning success and the relief of those responsible for education are very good.

On the other hand, new areas of tension are also emerging. Through empowerment and self-regulation, demands for personal development can come more to the fore («my development goals»). And the question arises as to which mechanisms, measures and offers can be used to create a good fit with the requirements of the company or organization. Here again, new tasks and challenges arise for those responsible for education and personnel development: in view of greater degrees of freedom (empowerment), other unifying bonds are needed. In addition to a common understanding of goals and strategies – broken down to different organizational levels – culture and value development will play an important role…

References:

Euler, Dieter (2018): Personalisiertes Lernen an Hochschulen. Keynote Vortrag. Kurztagung „Personalisiertes Lernen an Hochschulen – Wie viel darf es sein?“. Pädagogische Hochschule Zürich, 25.04.2018. Online verfügbar unter https://phzh.ch/de/Weiterbildung/Hochschuldidaktik-und-entwicklung/events/kurztagung/.

Kara I. (2020): How Hilti is redefining the role of L&D in the connected world. Linkedin.com. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-hilti-redefining-role-ld-connected-world-kara-ikaneng/

Keller, John M. (1987): Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design. In: Journal of Instructional Development 10 (3), S. 2–10. DOI: 10.1007/BF02905780.

Der Autor:

Dr. Christoph Meier

Dr. Christoph Meier

is managing director of scil at the University of St.Gallen. He supports educational organizations in coping with the digital transformation, the further development of education management and the competence development of employees. He is also active as a specialist coach and as a specialist speaker or learning facilitator in the scil academy’s certificate and diploma programs.

Contact:

Christoph Meier

swiss competence centre for innovations in learning

Universität St.Gallen

christoph.meier@unisg.ch

www.scil.ch